The Man From Mansi

His legs have yet to betray him. Where have his legs taken him during these 9 decades of walking on this earth.

Right now, he’s taking me to see his chickens up the stairs.

Walking towards the birds, we passed by about a dozen trees. He’s nurtured a fruit-bearing garden in his backyard.

Plums, peaches, apples, olives, lemons, and grapes. Yum. I feel at home.

“You have beautiful trees, ammi”, I expressed.

“Thank you. This came out of our need to be self-sustaining”, he explains. “You don’t know what will happen tomorrow”.

The birds sprinted out of their coop towards the shade of the fig tree, welcoming their caretaker with enthusiasm. He shows me the two types of chicken he has. The local chicken, baladi, which are smaller in size, and the brahma chicken, often called the chicken of chickens, a larger breed that carries a distinguishable feature of feathery legs and tasty eggs.

Amo Mohammad was born in Al Mansi, a village in the north of Palestine southeast of the city of Haifa. It’s known for its nearby springs, its agricultural lands, and overlooks the plains of Marj Bani Amer. In April of 1948, the village was occupied by Jewish forces. Within days, the people of the village fled and took refuge in neighboring towns, and the village of Al Mansi was destroyed. After several months of moving from one village to another, Mohammad, still within a decade of age, found work with his six cows in the Ghor, the valley of the Dead Sea.

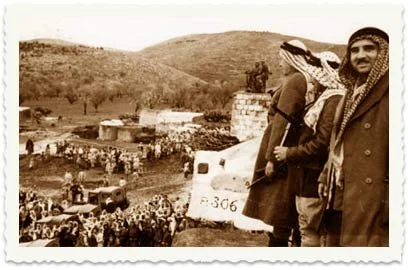

Fawzi Al Qawuqji, soldier and Arab nationalist, giving an announcement to the inhabitants of Al Mansi, about the war in the nearby settlement of Mishmar Ha Emek circa 1948. Taken from www.palestineremembered.com

A 1922 image of the town of Al Mansi. Taken from www.palestineremembered.com

His daughter, Fatina, appears behind us. She points out that the peach tree is still unripe. They discuss that it will be ripe soon, inshallah.

She directs my attention upwards towards the top of another tree. I look up and see a sturdy tree house.

“My kids loved that tree house. They were so excited when they found it there for the first time”, she says.

“You’ve had many memories in this house”, I noted.

“Oh yes, we would come here in the summers from Saudi and my kids would play here all the time”, she answers.

I start imagining children running around the trees, hugging parents and grandparents in this small garden of Eden; laughters and giggles in the tree house. There was life here, and there still is.

Despite its sturdy appearance, the tree house seems to be closed up.

“It’s now used for the pigeons”, she mentions.

The grandchildren have grown up now. Fatina’s children are working now and have been educated in some of the finest universities in the world.

“My father would always insist on one thing: education”, she states.

“They may take away everything, but they can’t take your brain, your thoughts, your ideas”.

Mohammad was offered the opportunity to live with his uncle and complete his secondary studies at the Jenin refugee camp, where UNRWA established a school. Despite its difficult living situation —difficult is surely an understatement— Mohammad went to school and devoted his time to studying. He saw that education was the opportunity to grow and make something of oneself. Whenever he would get distracted, he would remind himself to return to studying.

His hard work paid off. He graduated the first out of all the UNRWA schools in Jordan, which included the West Bank at the time. Having received this honor, he went to Amman to accept a full scholarship to the American University of Beirut to study the discipline of his choice. His choice? Medicine. He was to leave the refugee camp to be a student in the thriving cosmopolitan city of Beirut.

Below the tree house, I notice a couple boxes, making a discreet but noticeable buzzing noise. The boxes were sky blue, and they were lifted off the ground. Amo and I stood near them, under the olive and almond trees, observing.

“These bees make about 10 kg of honey a year”, he proudly states.

“How would you describe the honey?”, I asked.

“The flowers in Dahyet Al Rasheed produce rich, thick, and golden honey”, he describes to me.

“The beekeeper says that there are various roles for bees. There are those who protect the queen, those who protect the hive, those who clean out the dead bees and dirt, those who feed the baby bees, those who collect nectar, and the list goes on.” His admiration for these creatures was apparent in his lifted tone of voice.

With that admiration, I saw that perhaps he saw himself as a bee, fulfilling a role in the life that he lived among his family, his friends, and society: the role of a caretaker and provider. During that moment, I found a renewed admiration for the bees, and a new admiration for him.

When I came to photograph him at that moment, and as he was looking at those bees, there was a feeling that I could not shake off. With all that love and care that I saw in his eyes, I also saw a man who has experienced great difficulty.

It was a culture shock to move between such drastic environments, but Mohammad thrived. He thrived in the first two years of school so much, he started participating in the university’s civil society, political parties working to liberate Palestine. Of course, the government did not like this, and immediately deported him among others back to Amman with a suspended scholarship and no way to return.

With the will to complete his studies, Mohammad figured out a way back to Beirut without his legal papers. For 6 years, without legal papers, Mohammad figured out a way to work, figured out a way to graduate, figured out a way to get married and figured out a way to have a baby daughter.

With a degree in one hand and a newborn baby in another, now Dr. Mohammad, set out to leave Beirut.

Dr. Mohammad had the option to leave through the Beirut port, where he has heard stories of people either being caught by the sea, or by the authorities. For him and his family, these were not real options. He decided to go the most direct way, to sneak right behind the border officer leading into Syria. And that is what they did.

Everything leading up to him returning to Amman seemed like a test from God to see if he was up for being a doctor. Dr. Mohammad went to the United States to obtain his board certification and returned to the Arab world to work in Eastern Saudi Arabia for most of his professional career, at Saudi Aramco.

Dr. Mohammad and I go back downstairs to take his portrait. I photograph him standing in the paved way that leads into the verdant outdoor sitting area, surrounded by succulents, flowers, and lemon trees. Dr. Mohammad shows me a smile only a grandfather can offer. A smile full of care, love, and comfort.

With the Amman heatwave in full stretch, we quickly went back inside the house to cool off. At the entrance of the house were three small plants on the ground.

“These are taken from my wife’s mother’s home from 1970. We like to propagate them every now and then”, he explains.

“These give out a really beautiful and fragrant flower, isn’t that right Amo?”, I asked.

“Yes, yes they do”, he answers.

As we sit down to have some fresh lemon and mint juice, Khalto Um Amin hands me a bowl with some rocks painted with colors forming the Palestinian flag and the map of Palestine.

“These were painted by my grandchildren. They gave them to us as gifts”, she proudly explains.

If there is one thing he taught his children, it is the fact that they must work harder and be better because they are Palestinian. This relentless work ethic and striving for excellence him and his wife nurtured was evident in his children and grandchildren, all growing to be leaders in their fields, whether that be in medicine, in engineering, or in business.

Dr. Mohammad now lives with his wife between Amman and Dhahran, between a vibrant social life and solitude, between mediterranean fruits and desert dates. They’ve raised children, grandchildren, and now, great grandchildren. With a life usurped by occupiers, Dr. Mohammad chose to create his own through hard work, persistence, care, and companionship.

It was an honor to sit down with Dr. Mohammad Al Ahmad, Ms. Fatina, my former teacher and educator, and Khalto Um Amin for her kind spirit and supportive energy.